Finding Your Roots

Dreaming of a New Land

Season 5 Episode 4 | 52m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

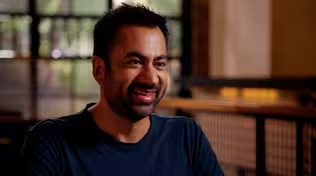

Dr. Gates reveals the family history of Kal Penn, Sheryl Sandberg and Marisa Tomei.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores with Marisa Tomei, Sheryl Sandberg and Kal Penn the tremendous challenges faced by their immigrant forebears. From Italy, Russia and India to America, their histories show success could take generations to achieve.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Dreaming of a New Land

Season 5 Episode 4 | 52m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores with Marisa Tomei, Sheryl Sandberg and Kal Penn the tremendous challenges faced by their immigrant forebears. From Italy, Russia and India to America, their histories show success could take generations to achieve.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGates: I'm Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Welcome to "Finding Your Roots."

In this episode, we'll meet actor Marisa Tomei, author and executive Sheryl Sandberg, and comedian and activist Kal Penn... Three Americans whose families were shaped by their immigrant ancestors... Tomei: "No friends no address no money."

Gates: He came to this country with nothing.

Sandberg: They traveled steerage class and the journey was so hard.

They didn't have enough food or water.

They had to beg from the upper-class passengers.

That's amazing.

That's why I'm here.

Penn: This reinforces the beauty of what it means to be American.

Gates: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool available... Genealogists help stitch together the past from the paper trail their ancestors left behind, while DNA experts utilized the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets hundreds of years old.

Penn: Wow, that's awesome!

Gates: And we've compiled it all into a book of life... one copy in the whole world!

Tomei: Just one in the whole world... Gates: A record of all of our discoveries... Sandberg: Amazing!

Penn: Going back that far, that's like, getting a little emotional thinking about it, you know, it's cool.

Gates: Marisa, Kal, and Sheryl's roots stretch to disparate corners of the Earth.

but they also have something in common: ancestors who arrived in the United States with little more than a dream, but who laid the groundwork for their success.

in this episode, they are going to retrace the journey those ancestors took, glimpse what they left behind in their homelands, and discover why their stories still inspire today.

[ Theme music plays ] ♪♪ ♪♪ Immigration is the lifeblood of the United States.

Our vital force, drawn for centuries from all over the world... producing a nation of vast diversity... and shaping each of us in ways both great and small.

For actor Marisa Tomei, who grew up in Brooklyn, surrounded by the children and grandchildren of immigrants, America's diversity has proved a constant source of inspiration... Tomei: I always had friends of all ethnicities, and I think that really influenced me as wanting to be an actor, and... Gates: Hm.

How?

Tomei: Oh, gosh, being in my next-door neighbor Mary's home and staying home with her to bake cookies, because she was Greek, and learning all about the Greek holiday, and uh going over to my best friend Kelly's house, uh, for Shabbat on Fridays and lighting candles with her.

Gates: Oh, that's cool.

Tomei: And it just made me really appreciate... Gates: Difference?

Tomei: Difference and similarity and just, just humanity.

Gates: Surprisingly, though Marisa knew that she herself was descended from recent Italian immigrants, it wasn't central to her identity.

Partly because her roots weren't often emphasized in her home.

When did you start thinking of yourself, we're Italian?

Tomei: It took a while.

I didn't really think about it.

I thought that I was Jewish for a long time because of my neighborhood.

It wasn't until I started going on auditions, as I set out to be an actress and was told things like, well, you, you can't be in these commercials cause you're too ethnic.

Gates: Really?

Tomei: And I started thinking, well, what does ethnic even mean, and what am I?

Gates: Marisa's question was answered, at least in the public's mind, when she was cast as Mona Lisa Vito, a fast-talking Brooklynite, opposite Joe Pesci, in "My Cousin Vinny"... Tomei: My niece, the daughter of my sister, is getting married.

My biological clock is tickin' like this and the way this case is goin', I ain't never gettin' married.

Gates: It was a breakout performance, winning Marisa an Oscar, and making her one of the most recognizable Italian Americans in Hollywood.

Even though her connection to her own heritage remained elusive.

Tomei: Even speaking with that heavy Brooklyn accent uh was almost an offense to my mother and the way that she had raised us.

But, of course, the character is actually very smart.

Gates: Yeah.

Tomei: Just in a different kind of package.

Gates: Yeah.

Yeah.

Any of your traits do you think are traceable back to your ancestors?

Tomei: Well, I do believe that, that there are things like cellular memory, but I don't know enough about my own really deep, uh, family history to know what I'm carrying.

Gates: Well, that's about to change.

Tomei: That's about to change.

Yeah.

Gates: You dropped into the right address.

Tomei: Yeah.

Yeah.

Gates: My next guest is Sheryl Sandberg, the COO of Facebook, and a bestselling author.

Unlike Marisa, Sheryl grew up very aware of her immigrant roots.

Her parents families came from Jewish communities in Eastern Europe.

And throughout Sheryl's childhood, they were active advocates for Jewish people still trapped behind the Iron Curtain.

So active, in fact, that they almost lost their own freedom.

Sandberg: My parents went on a trip to the Soviet Union.

That was not a common thing to do.

It wasn't a huge tourism industry then but they went to go try to help Soviet Jews.

So they were going in to get records and names of here are the families that have applied for exit visas.

So they've become "refusniks' because when they had names and pictures of these are families they would get protected by the virtue of people in the West knowing who they were.

Gates: Oh, that's interesting.

Sandberg: And so they were arrested by the KGB, which makes them two of the only Americans that have ever done that.

Gates: It's amazing.

They were detained by the Soviet police for ten hours and you were five years old!

Sandberg: Yes, and my mother pretended she had her period, went to the bathroom and flushed all the notes down the toilet.

Gates: She did?

Sandberg: She tried to memorize the names.

Gates: That was brilliant.

Sandberg: Yeah.

my dad was very proud of her.

We're very proud of that story.

Gates: Sheryl's pride in her parents spills over into almost every aspect of her life.

She's remarkably devoted to them, and to the values that they instilled in her, values that she says were passed down from their immigrant ancestors, a devotion to hard work, education, and, above all, to family.

Sandberg: I was raised with what my grandma told my mom, which was your siblings are more important than your friends, you know when you're fifteen you're super nice to your friends and not that nice to your siblings.

That was not tolerated in my house.

There was no being nicer to your friends than you were to your siblings.

Gates: Huh.

And you actually did that?

Sandberg: There was no choice.

But my parents would say your siblings are going to be with you for the rest of your life.

Gates: Sheryl told me that her parents' lessons grounded her and gave her a strong sense of self which would serve as an invaluable asset in navigating the male-dominated culture of Silicon Valley.

They also helped guide her through an immense tragedy.

In 2015, Sheryl's husband, Dave Goldberg, died suddenly, leaving her alone to raise their two young children.

Grief-stricken, she found solace and strength in the bonds that had been forged in her childhood home... Sandberg: The first time I went back to the grave was what would have been Dave's birthday, the first birthday he missed, and I'll never forget this.

I'm kind of sitting on the ground by myself and my brother and sister came and sat down next to me.

My parents were behind and we're at this grave where I think we may all be buried one day.

I thought to myself, wow, my brother and sister were in my life long before Dave, my husband, and with any luck they're going to be in my life long after my parents.

These are my people.

And other people can be my people too but there is something about family.

Gates: My third guest is the comedian, actor and activist Kal Penn... Kal's experience with immigration is much more recent than Sheryl's, or Marisa's... His father came to America from India in the 1960s, to pursue a career in the sciences, his mother followed soon after... They settled in suburban New Jersey... where their son's ambitions posed a challenge... Did your parents want you to be a scientist?

Was that the thing, perhaps?

Or no?

Penn: I think there was always an, a hope or expectation, if not a little pressure, um, to pursue fields like medicine, science, engineering, things that were both stable and also what my parents knew.

Gates: Sure, same with my parents.

Penn: Yeah.

I mean I remember in tenth grade, telling my dad I want to be an actor or a musician.

He's like, "I did not move here with $12 in my pocket for that."

Gates: Despite his parents' anxieties, Kal was determined to pursue a career on the stage.

But it wasn't just his mother and father who had to be convinced, he was also getting resistance from people in his community.

Penn: When there were family-friends get-togethers, you'd go around the, go around the room, and they would ask some, somebody "What do you want to be?"

"Well, I already got into Hopkins early, I'm going..." Gates: "I'm gonna be a brain surgeon."

Penn: Like, "I'm in the BU seven-year program, and they would get to me, "What do you want to do?"

"I want to be, uh, I want to be an actor."

Gates: They'd say, "You're so funny."

Penn: People would laugh.

"No, really, what are you gonna...?"

I'm like, "I want to be an actor."

and somebody would go and console my parents, like, "I'm so sorry.

You know, we'll talk to him," and then legit, they would have, they would have, like, the older cousin's friend come over and talk to me, and be like, "You know, I was like you too, I was in a band in high school, but you know, now I'm a neurosurgeon, and you might want to consider what you want your life to be like."

Gates: "And I'm rich."

Penn: Right.

You know, we can joke about this now, but at the time, of course it was an incredibly tough, sort of painful thing to deal with, where you're caught between not understanding why your parents' generation of, of friends and aunts and uncles feel this way.

They're recent immigrants.

The life that they know of prosperity is very much tied into stability.

Then you're from a generation where you're born and raised in a country where you hope that anything is possible, um, and so, when those two things come together, it's confusing as a kid.

Gates: It's hard to picture Kal as a confused kid.

He's built a remarkably successful and varied career.

Moving fluidly between acting in off-beat comedies, prestige dramas, and performing public service, he even took a hiatus from Hollywood during which he served in President Obama's Office of Public Engagement.

Penn: Look at all these accomplishments that the president has had for young people.

College affordability, two and a half million of them now have health insurance that didn't before.

Gates: Along the way, Kal has not only won over his parents, he's come to appreciate that their fears for his career were based on their experience in coming to America.

An insight that motivates him, even today.

Penn: I mean, the sacrifice that both my parents, made to come to this country, to, uh, to, you know, sort of your cliché immigrant story, but in search of a better life, uh, to decide to put down roots here and have kids here, and start a family when the family that you know is literally halfway around the world, um, is pretty bold.

Gates: Yeah.

Penn: I mean that's pretty amazing.

Gates: Meeting our guests, it was clear that each knew that their families, and indeed their careers, had been shaped by immigration.

But as we began investigating their roots, it was also clear that many of their family stories had been lost on the journey to America.

It was time to recover them... I started with Marisa, and her maternal grandmother, whom she never really knew.

You know who that is?

Tomei: I don't know who that is.

Gates: That's your grandmother in her early 20s.

Tomei: I've never seen this.

Wow.

Gates: Maria D'Ignoti.

Tomei: D'Ignoti, D'Ignoti.

Gates: D'Ignoti?

Okay.

Tomei: Yeah, Maria D'Ignoti.

Gates: D'Ignoti.

Tomei: D'Ignoti.

Gates: D'Ignoti.

I'll do my best.

Your grandmother Maria died shortly before your third birthday.

Do you have any memories about her when you were growing up?

Tomei: Uh, not vivid ones.

I have a sense of her, you know?

More of a feeling memory.

I remember she liked to laugh a lot.

That's probably where that comes right down from.

Gates: Yeah?

Tomei: Yeah.

Gates: Marisa's grandmother was the child of Italian immigrants, and Marisa believed that they'd come from Sicily, where she'd heard that Maria's father Giacomo had grown up in desperate poverty.

She wanted to know if the stories were true.

Our search led us to Messina, a Sicilian port, where we came upon a familiar name... Tomei: "On the 4th of January of the year 1887, in the municipality of Messina was born D'Ignoti, with a D apostrophe Ignoti, Giacomo, son of Anton... Antonino, son of Antonino, age 28, and Buta Francesca."

Gates: That's the birth record you're looking at for your great-grandfather Giacomo.

Tomei: Wow.

Wow.

Gates: This record was crucial because it not only placed Marisa's ancestors in a specific locale, it also gave us the name of her great-great grandfather: Antonino D'Ignoti.

And he would turn out to be the lynchpin in her family's story.

Antonino was a carpenter, born in the late 1850s.

By the turn of the 20th century, he was living in Messina, married with six children.

At the time, Sicily was among the poorest places in Europe, beset by hunger and social unrest.

So Antonino took a chance, he set off for America.

The odds were stacked against him.

He arrived with only $10 in his pocket, and immediately, he was detained.

Tomei: Welcome.

Gates: Yeah, welcome, give me your tired, your poor.

Tomei: Yeah, very different.

Very different.

Gates: Antonino is your original immigrant ancestor on this line of your family tree.

Tomei: Okay, wow.

Gates: And coming in 1902, he is the person who brought this part of your family to America.

Tomei: Wow.

Gates: And he came to this country, nothing.

Now, when immigrants came here with no money, like your great-great grandfather, it was common for them "boy you're in the wrong place.

You're gonna go back home."

To be deported right away.

And as you could see, Antonino was held for inquiry.

Tomei: Uh-huh.

Gates: So they likely considered deporting him.

But they decided to let him in, and that changed your family's fortunes.

Tomei: This is incredible.

Gates: Antonino D'Ignoti was over 40 years old when he arrived in New York, but he seems to have had the energy of a much younger man.

He soon found work, and then he began to bring his family over from Sicily.

Within eight years, his wife and all of their children had crossed the Atlantic.

Their story is common among immigrant families, but that doesn't make it any less impressive.

And as we dug more deeply, we realized just how far the D'Ignotis had actually come.

This is your great-great-grandfather's death record from 1912.

This record names your third great-grandparents, your great-great-great- grandparents, Antonino's parents.

Tomei: Whoa.

Gates: And do you see what it says about his father's last name?

Tomei: Uh, it's unknown.

Gates: Unknown.

What do you make of that?

Tomei: I don't know.

Uh, I don't know.

Gates: Well, we consulted an expert in Italian genealogy and he told us something fascinating.

Literally, "ignoto" means unknown, literally.

Tomei: Uh-huh.

Gates: And your third great-grandfather Giacomo's surname "D'Ignoti" translates as quote "of the unknown ones" or "of unknown parentage."

Tomei: Oh my God.

Wow.

Wow.

Gates: It was an identifier given to babies who had been abandoned.

Tomei: You know when I saw it with the apostrophe D for the first time, I was like what does this word mean, it must mean something, and I... Gates: That's what it means.

Tomei: Uh-huh.

Wow.

Gates: "Of unknown parentage."

Did you have any idea of the origins of that name?

Tomei: No.

No.

No, not at all.

Gates: We can't say for certain whether Antonino himself was abandoned as an infant, or whether the name comes from a more distant ancestor.

We only know that this branch of Marisa's family tree appears to have begun with a foundling child.

And we have an idea of what that child experienced, because Sicily's landscape still bears evidence of a once painfully common event... Would you please turn the page?

Take a look at that.

Any idea what that is?

Tomei: Uh, maybe it's like a church... All right, I'm thinking it's like a church window where you put your baby.

Gates: Brilliant.

Yeah.

Tomei: Really?

Gates: A hundred... Tomei: I mean it looks like a prison, but it looked like... Gates: Well, it was, it was literally called a foundling wheel.

You ever hear of a foundling wheel?

Tomei: No.

Gates: In the early 1800s, roughly 7% of the babies in Sicily were abandoned, obviously because of the crushing poverty in Southern Italy.

Tomei: Yeah, the crushing, crushing, crushing poverty.

Gates: You know, your ancestors paid their dues.

Tomei: Yeah.

That is, uh, is deep.

Gates: My next guest is Sheryl Sandberg.

Sheryl grew up hearing stories about her immigrant ancestors from Eastern Europe... On her mother's side, those stories often centered around her great-grandmother, a woman named Minnie Schupper.

Minnie came to America as a child, traveling with her mother, who kept a journal of their experience.

It's a central event in the family's history.

But Sheryl had never seen any documentation of it, until now.

Sandberg: This is the S.S.

"Taormina" passenger list from 1889.

Gates: That is the ship that your ancestors came to the United States on.

Sandberg: It's not the Mayflower.

Gates: No.

It's not the Mayflower.

Would you please read who's on board?

Sandberg: "Chana Schupper, 30 years old.

Solomon, eight years old.

Mandal, six years old.

and I think Minnie, eleven months old."

Wow!

She was eleven months old.

Gates: So you've heard the stories?

That's the moment.

Sandberg: That's amazing.

That's why I'm here.

Gates: And that baby girl is your great-grandmother, Minnie.

Sandberg: Um-hum.

Gates: Listed on this document alongside Minnie are her mother, Chana, and her two siblings.

Minnie's father isn't listed, he'd come to America a year earlier to find work forcing Chana to cross the Atlantic on her own, caring for three young children... It was a harrowing experience, Sheryl told me that reading about it in Chana's journal made a lasting impression... Sandberg: They traveled steerage class, people got sick.

They were on the bottom bunk.

People would throw up below them.

They didn't have enough food or water.

They had to beg from the upper-class passengers and then she said that what was so hard for her was her children got on the boat immaculate and clean and they got off the boat filthy and covered with vermin.

Gates: Can you imagine?

Sandberg: No, she was a very strong woman.

Gates: You know, I think about it in terms of the Middle Passage.

You know, I don't even like crowded elevators.

I mean how in the world could I have survived a slave ship?

But somebody did.

Otherwise I wouldn't be here.

Sandberg: That's right.

And your ancestor did.

Otherwise you wouldn't be here.

Not just someone.

Your DNA.

Gates: My DNA.

Sandberg: I've studied strength now, after my husband died.

I've studied resilience and it's interesting because it's part of who we are, but we also build it.

And we built it in each other.

You know, there was someone on that ship who was traveling first class who gave my great-great-grandmother food, which is why they survived across that ocean.

Gates: Though Sheryl knew about her ancestors' journey to America, she didn't know exactly where they came from.

She'd been told that they were Russian, and we were able to verify that, tracing them back to the town of Vidzy, in what was once part of the notorious Pale of Settlement, where Russia confined much of its Jewish population, severely limiting their opportunities.

When Sheryl's family left, in the 1880s, poverty here was widespread, and that's almost certainly what drove them away... Do you feel a connection to this town?

I mean you have deep roots there.

Sandberg: You know I didn't know the name of the town, so I don't think I had felt a connection.

I feel a connection to them more than the town and it may be because I assumed that they left because of anti-Semitism so it's pretty hard to feel a connection to a town that pushes your family out for discrimination.

Gates: Right.

Sandberg: I would say I feel very lucky.

I think like any Jew who's alive you know that your ancestors were not killed in the Holocaust.

And if you are descended from Europe that's what would have happened and so the bravery of these people got them out and saved your life.

Gates: If they made the choice.

Sandberg: If they made the choice.

Gates: Sheryl's intuitions are correct: her ancestors made a very fortuitous decision to leave Vidzy.

Almost the entire Jewish population of the town was murdered during the Holocaust... Few records of that population survive.

In fact, for many Jewish people from the region, there were no records at all.

But Sheryl's family provided an exception.

We found a document that shed light on her deeper roots... Sandberg: Whoa!

Gates: This is a tax record, dated September 27, 1846.

Sandberg: "Name: Itsik.

Father: Schacno.

Surname: Klumel."

Gates: That's your 4th great-grandfather.

and you just met his father... Sandberg: Your fifth, my fifth great-great... Gates: Your fifth great-grandfather!

Sandberg: That's amazing.

Gates: You got it.

Sandberg: I can't wait to show my parents this.

Gates: Well, that document records what's known as a candle tax.

Any idea what a candle tax might be?

Sandberg: It must have been a tax on candles.

I don't mean to be too literal.

Gates: You're a genius.

It was a tax on the candles used in Sabbath ceremonies.

Sandberg: Oh so, it's a tax for Jews.

Gates: Tax on Jews.

Sandberg: Yeah tax on Jews.

Unbelievable.

Gates: Throughout Europe, going back to the Romans, special taxes were imposed on Jews.

There were "meat taxes," which taxed the sale and slaughter of kosher meats.

Some countries even had "tolerance taxes," that Jewish people had to pay simply to be tolerated.

Sandberg: Tolerance taxes?

That's unbelievable.

That's worse than a candle tax by a lot.

Gates: Oh, it's the worst, it's the most perverse tax I ever heard of in my whole life.

I often wonder how, how did Jews survive?

What keeps a suppressed group believing in the future?

Sandberg: I'm not an expert on this but one of the answers that I wrote about is that as an individual facing tremendous challenge there are moments where you lose hope but the person next to you keeps hope alive.

Sometimes it's when someone else is down that you can extend that I'm going to believe for both of us.

You don't have to believe today.

You'll believe tomorrow.

Gates: So that's why traditions are important.

Sandberg: And community, family, community ties.

Gates: My third guest is Kal Penn.

Unlike Marisa and Sheryl, his immigrant ancestors weren't distant figures who had arrived from the Old World on steamships.

They were his parents, who came by plane, and settled in suburban New Jersey, followed closely by their parents, on both sides, all of whom lived in America for a time.

So Kal knows firsthand the sacrifices immigrants make when they leave their birthplaces behind.

And he experienced himself the challenge of feeling like a stranger rather than a native son.

Penn: When people say, "Where are you from?"

it's often an othering statement, right, that what they mean is, "You are not somebody who I'm familiar with."

Gates: I know they look at you, look at that brown face, who are you?

You know, "Where are you from?"

How do you answer?

Penn: I always say New Jersey.

I do, because it's truthful that I'm from New Jersey, that's where I was born and raised.

Gates: Was there a day when you became an Indian, you know?

Every autobiography in the black tradition... Penn: Yeah.

Gates: ...has a moment when you discover that you're black.

Penn: Yeah.

Gates: And it's not a good day, right?

You are reminded of your difference and discriminated... Penn: Yes.

Gates: ...because of that.

Did that ever happen to you?

Penn: I mean, I don't think there was a day that I was not aware of it, going back to elementary school, when there was an Iranian-American kid, uh, not even in my class, but in my grade, and people would confuse us all the time.

Teachers would confuse us all the time.

I'm like, "We look nothing alike.

He happens to be brown."

Gates: Right.

Penn: Haircuts are totally different, I'm taller than this dude, and you know, we get called each other's names.

And I remember being confused by it, because I thought teachers are supposed to be smart, how can you be that stupid?

And then middle school was probably the first time where I realized, "Okay, this is, this is a real thing for somebody."

Gates: Growing up, struggling to fit in and find himself, Kal was especially inspired by his maternal grandfather, a man named Indravadan Bhatt.

Indravadan was a teacher, a lover of literature and storytelling, and, in his youth, an activist who had marched with Gandhi.

He set an example for Kal, connecting him to his family's past, while also pointing him towards the future.

Penn: My grandfather used to have this photo of Gandhi hanging in his house, and uh, and I remember, from the time I was a little kid, I remember seeing the photo, and I would hear stories about it.

And after they passed away, you know, uh, I said, "What's happening to that, that photo?"

They said, "Well, why don't you take it?

You have the biggest connection to it.

You've always had a thing for it," and I had a chance to hang that on my wall, uh, in my office at the White House.

Gates: Oh, that's cool.

Penn: Uh, as just sort of a, just a reminder, you know?

Gates: Yeah.

I wanted to help Kal better understand his grandfather's connections to Gandhi.

They were more extensive than he knew.

The story began in 1918, in the town of Amod in Central India, where Indravadan grew up.

At the time, India was a British colony and Gandhi was agitating for independence, building a movement that focused on the fact that India was required to import British cloth at inflated prices.

Gandhi was encouraging Indians to spin their own cloth, called khadi, and to wear it in public as a protest against the injustice of colonial rule.

His movement soon drew attention from around the world.

Any idea how your family responded to Gandhi's call to action?

Penn: I assume they made a bunch of cloth.

Gates: Could you please turn the page?

You know who that is?

Penn: No.

Gates: That's Indravadan, that's your grandfather.

I want you to take a close look.

Look at those white clothes that he's wearing.

That's khadi.

Penn: Wow.

That's nuts.

Gates: And by wearing khadi, your grandfather was making a bold statement against imperialism.

Isn't that cool?

Penn: Yeah.

That's awesome.

Gates: You just think, the fabric of... Penn: Yeah.

Gates: ...of your suit would be a nationalist, that's cool, man.

Penn: That's cool.

Gates: Gandhi was such a genius.

Penn: That's really cool.

Gates: Kal, your family told us that your grandfather continued to wear khadi for the remainder of his life.

Do you remember that?

Penn: I do remember that he, um, that he would always wear white, except when it was cold in New Jersey, and there would be a sweater on top of it.

Gates: Indravadan took a risk in following Gandhi, and wearing khadi was only a small part of that risk.

In 1930, Gandhi passed through Amod on his famed Salt March, a protest against British efforts to prevent Indians from collecting and selling their own salt.

We believe Indravaden joined this march, which was soon confronted by British police outside the town of Dharasana... Penn: "Police charged, belaboring the raiders on all sides.

The volunteers made no resistance.

As the police swung lustily with their sticks, the natives simply dropped in their tracks.

With almost unbelievable meekness they submitted in the clubbing and were carried away by their comrades who had collected a score of stretchers."

Gates: Now, we don't know if your grandfather was at Dharasana that day.

Your family told us that he suffered a beating, though... Penn: Yes.

Gates: ...during a protest.

Penn: He did tell me a story about getting beaten by British soldiers.

I think he still had a scar on his leg, if I'm not mistaken, and that was, I think, the only time I ever saw him shed a tear.

Gates: Really?

Penn: Was recounting that story.

but reading this account... I feel like it's giving me a very, I feel like a clear participant in something that previously was only a chapter in a history book.

Gates: Yeah.

Penn: It's really cool.

Gates: Kal wanted to know about Indravden's roots.

We were able to identify his parents, Kal's great-grandparents, Dhanlaxmi and Chotalal Bhatt.

Both were born around 1880, likely near Amod.

But that's where the paper trail ran out, and, for a time, it seemed that was all we would ever be able to find.

Genealogy in India is notoriously difficult due to a lack of records and irregular naming practices... To go further, we needed a break.

Fortunately, we got one.

Our researchers discovered that Kal's mother's family has long maintained an oral history.

That history traces his maternal roots back nine generations in an unbroken line, all in and around the town of Amod.

Look at those, read those names for me.

Start with you and go up.

Penn: "Kalpen Suresh Modi, Asmita Indravadan Bhatt, Indravadan Chhotalal Bhatt, Chhotalal Ranchoddas Bhatt, Ranchotlal Bhatt, Governan Bhatt, Kashiran Bhatt, Duljiran Bhatt, and Kasanji Bhatt."

Gates: That's your great-great-great-great-great- great-great-grandfather... Penn: That's awesome.

Gates: Kasanji, who was likely born around the year 1700.

Penn: Wow.

Gates: You have DNA from all those people.

Penn: That's awesome.

Gates: That's amazing.

Penn: That's cool.

Gates: it's a whole lot of Bhatts.

Penn: It is, yes.

Gates: Yeah.

You're a New Jersey branch of something.

Penn: No, exactly.

Right.

Gates: Deep, deep roots.

Way over in Amod.

Now, that's heavy.

Look at that, continuous.

Penn: Going back that far, that's like, I'm getting a little emotional thinking about it.

You know, that's cool.

Gates: Well, you have every right to be emotional.

I mean, those are your people, man.

Penn: Yeah.

Gates: Does it make you feel more Indian, to put it in a vulgar American way?

Penn: I actually think it, it makes me feel a lot more global, and i hope that doesn't sound trite or cliché... Gates: No, I like that.

Penn: But I feel like my sense of patriotism as an American is in that foundation of we are all from somewhere, and that's what makes us beautiful and unique in... Gates: We're all from somewhere else!

Penn: Right, that's what I, right, we're all from somewhere else.

And so, this is just more of that context, having those stronger roots makes me feel more American in an interesting way.

Seeing these names going back to 1700 now that feels really empowering.

Gates: We had already taken Marisa Tomei's maternal roots back to Sicily, where the paper trail ended in the 1850s.

Turning to her father's side of her family tree, we were able to go back even further.

Our journey started with Marisa's grandmother, Rita Calvosa, who was born in Brooklyn in 1918.

The child of two Italian immigrants, struggling to gain a foothold in America.

Her father Albert, a garment worker, died when Rita was only eight.

The tragedy left the family in turmoil, and Albert's story had been largely forgotten.

Marisa didn't even know where in Italy he had come from.

We found the answer in his naturalization papers... Tomei: "Albert Calvosa.

I was born in San Demetrio, Italy.

I emigrated to the United States on the vessel 'Columbia' on June 1891."

Gates: You ever hear of San Demetrio?

Tomei: No.

Gates: It's part of the Calabria region of Italy, and it's the town indicated on the map to the left.

Tomei: Uh-huh.

Gates: That's where your great-grandfather Albert was born.

Tomei: Wow.

Gates: Did you know that?

Tomei: No, I didn't know that.

Gates: Calabria is the very southernmost region of the Italian Peninsula, and much like its neighbor Sicily, it's historically suffered from systemic poverty.

Records in this area can be difficult to access, leaving many Italian-Americans with questions about their Calabrian ancestors.

But with Marisa, we were fortunate.

We found a series of birth and marriage records, taking us back to her third great-grandparents, and providing a telling detail about their lives... Tomei: "Maria Theresa Cumano and Don Carlo Maria, royal chancellor."

Gates: Royal chancellor.

Tomei: Oh.

Just what a girl wants to hear.

Gates: Any idea what that might mean?

Tomei: No, but I like the ring to it.

Gates: Yeah, especially the royal part.

A royal chancellor was a government position.

And Marisa's third great-grandfather, Don Carlo Maria Corrado, served in a government headed by a very powerful man: Ferdinand II, a scion of the House of Bourbon, one of Europe's premier royal families.

Beginning in 1830, Ferdinand was the ruler of what was known as the "Kingdom of the Two Sicilies," the largest kingdom on the Italian Peninsula, and Don Carlo was part of his administration.

Marisa's family had clearly risen above the poverty that afflicted so many people in Calabria.

But their position was unstable... In 1848, Italy was caught up in a wave of revolution, as liberal nationalists attempted to unify the country and overthrow its many monarchies.

Suddenly, Ferdinand II was seen as a tyrant.

Which raised an interesting question... So, what do you think?

Were your ancestors in favor of the monarchy or in favor of social change of this unification movement?

Tomei: Oh, I don't know.

What did he do?

Gates: You gotta guess.

Tomei: I'm rooting for the side of the people!

Gates: Well, let's find out.

Tomei: Okay.

Gates: Would you please turn the page?

This is a document from a trial that describes a revolt in San Demetrio in that year of revolution, 1848.

Your third great-grandfather testified in court against a man named Don Raffaele Mauro.

Tomei: "In order to convince the people that the king was no longer relevant, Don Raffaele Mauro had the statue of the king shot by a firing squad, ordering that before the execution there should be a simulated trial and that a death sentence should be proclaimed!"

Not short on drama.

"According to the testimony of Don Carlo Maria Corrado, Don Raffaele Mauro ordered that the king's statue should be removed from San Demetrio and that after being paraded ignominiously through the streets of the town, amongst cries of 'death to the tyrant,' it was deposited in the guardroom in order to be shot by firing squad the next morning.

Don Carlo Maria Corrado claims that Don Raffaele Mauro displayed such despotism that he terrified the entire population."

Wow!

Gates: What's it like to see that?

It's testimony... Tomei: Wow.

Wow.

Gates: Isn't that cool?

Tomei: It really comes to life.

Gates: Yeah.

Tomei: Wow.

Gates: His opposition of revolutionary Mauro tells us that he rejected the liberal movement.

Now, are you disappointed?

Tomei: I am, really.

Gates: Yeah, but he was protecting his family, his income.

Tomei: Well, you have to give up something, sometime, sacrifice for the greater good, but... Gates: Marisa's disappointment was palpable, but the story wasn't over.

Ferdinand and his allies failed to crush the liberal movement, and in 1868, after more than a decade of strife, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies became part of a unified Italy.

Want to guess how your family fared in all this turmoil?

Tomei: Uh, I don't know how popular they were anymore in that town.

Gates: Well, we're gonna find out.

Tomei: Okay.

Gates: Would you please turn the page?

Marisa, this is a listing of many of the participants who supported unification.

Tomei: Who supported unification?

"Don Carlo Maria Corrado."

Gates: Yes.

Your third great-grandfather eventually turned on the Bourbon regime.

Tomei: Oh, okay.

Alright, come on!

Gates: Now, that make you feel better?

Tomei: Yeah.

Gates: We had now taken Marisa back two generations in Calabria, and revealed how her ancestors had navigated one of the most tumultuous periods in all of Italian history.

But a question still confronted us, how did the descendants of a former chancellor end up an immigrant in Brooklyn?

The answer was simple: economics.

Unification didn't bring prosperity to all.

In 1887, the Italian government imposed protectionist tariffs seeking to stimulate industrial development in the north, but wreaking havoc on the agrarian economy in the south, and driving Marisa's ancestors to emigrate.

Tomei: "State of New York, certificate and record of death of Raphael Calvosa.

He died on the 8th day of October, 1896, died of diabetes."

Gates: There's your great- great grandfather Raffaele.

He and his wife, Serafina, moved to New York with your great-grandfather Albert, see, we're making a circle, sometime in the early 1890s... Tomei: This is incredible.

I'm very, very, very grateful, the gift of not only a lifetime, many lifetimes, really.

Wow.

Gates: And these people will never be lost again.

Tomei: Wow.

Yeah.

That's a beautiful way to put it, thank you.

Gates: We had already traced Sheryl Sandberg's maternal roots back to a shtetl in the Russian Empire, and explored the journey her ancestors made to the United States.

Now, we had a different kind of story to tell, a story about the challenges immigrant families face even after they've crossed the Atlantic.

It began with Sheryl's grandmother, Rosalind Nuss, whom Sheryl knew well, and who was, by all accounts, quite a character... Sandberg: She was very strong.

She had cancer, breast cancer when she was young.

She survived.

She went on to raise a lot of money for other women to get mammograms because she was worried that poor women couldn't get them and that was what saved her life.

She did this by selling counterfeit watches out of the trunk of her car at the condominium.

Gates: She did?

Sandberg: Yeah, I wonder if I'm supposed to admit that.

Gates: That's cool.

No that's great.

Sandberg: But she had a, like a Buick and she would drive around the condominium and she had these fake Gucci watches and she would sell them for 30 dollars and they would break all the time and she had a little um, screwdriver and she would fix it right there.

She was a doer.

She was a huge doer.

Gates: Sheryl's written about Rosalind's life in some detail, and sees her as both as an inspiration, and as a precursor, for her own accomplishments.

But we found something that Sheryl hadn't seen before, something that tied the two together even more closely: Rosalind's college yearbook, which showed that she and her granddaughter shared the same major... You could see that she majored in economics.

Sandberg: I did not know that.

That's amazing.

Gates: You didn't know that?

Sandberg: I did not know that.

She grew up very poor.

So it was considered a very big triumph that she got to college at all.

Gates: Do you know much about her childhood?

Sandberg: I know some.

Her parents got divorced, but divorce in those days was unheard of.

They were very, very unhappy and she grew up... It was, I think, very hard.

Gates: Well, let's take a closer look.

Would you please turn the page?

1930.

This is the federal census for the Bronx.

Would you please read the transcribed section?

Sandberg: Yeah.

"Israel Nuss, rents his home for $35 per month, 47 years old.

Occupation: mail clerk in a post office.

Sarah, wife, 37 years old.

Florence, his daughter, 13 years old."

That's my aunt Florence, and "Rosalind, my grandmother, is 12 years old."

Wow.

Gates: This census introduces us to Rosalind's parents, Israel and Sarah Nuss, both were children of recent immigrants.

But they apparently had little else in common.

According to Sheryl's relatives, Israel was a difficult man, who ended up estranged from his children.

The reason, it seems, lay in his troubled childhood.

Sandberg: I don't know what happened.

I think the family did not stay close to him.

Gates: Why?

Sandberg: I don't know.

Gates: Your mother Adele has heard that Israel's parents were dying of cancer so they both committed suicide.

Sandberg: Oh, my God.

I never heard that.

Gates: You never heard that?

Sandberg: No.

Gates: Okay.

Well, we wanted to see if that was true.

Let's see what we found out.

Sandberg: Whoa.

Gates: This is a birth record from Manhattan dated April 13, 1883.

Sandberg: "Name of child: Israel Nuss.

Name of father: Dave Nuss.

Maiden and full name of mother: A. Ricka Nuss Blaschker."

Gates: That's your great-grandfather's birth certificate.

Sandberg: Whoa!

And these are his parents.

So they, and the story they, maybe they committed suicide?

Gates: We're going to find out.

Do you think it's true?

Sandberg: I hope not.

Gates: As it turns out, the family story was just that: a story.

Neither of Israel's parents killed themself.

But as we researched further, we realized it may have been easier to imagine the deaths were suicides than to accept the reality of what actually happened.

In 1898, Israel's father David died of cirrhosis of the liver, a condition most commonly associated with alcoholism, leaving his wife Ricka, also known as Frieda to face an even greater tragedy.

Sandberg: "Julius Nuss...died on the 28 day of August 1898, about 7:00 pm.

The cause of his death enterocolitis."

Gates: Julius was Frieda and David's youngest child.

Sandberg: So this is Israel's brother?

Gates: Yes.

Sandberg: Poor mother.

That's horrible.

Can't imagine.

Gates: That's horrible.

So three months after her husband died, Frieda's 10-month-old infant died as well.

Sandberg: Horrible.

Horrible.

Gates: Could you please turn the page?

Sandberg: Wow, so, "Hebrew Orphan Asylum Society of the City of Brooklyn.

Abe Nuss, 4 years old.

Louis Nuss, 11 years old.

Sarah Nuss, 13 years old.

Ike Nuss, 9 years old."

So they all go to an orphanage after the father and the little brother dies.

Gates: That's right.

Israel was not admitted to the orphanage.

This is likely because he was fifteen years old at the time and could find a job.

Sandberg: Wow.

Gates: The children were admitted three days after the death of her infant.

Sandberg: Right afterwards.

Wow.

Gates: Let's see what happened next.

Could you please turn the page?

This is another document that we found at the orphan asylum.

Sandberg: Oh, this is more hopeful... "Abe Nuss, discharged January 7, 1903, to mother.

Louis Nuss, September 13, 1901 to mother.

Sarah Nuss... December 2,1900 to mother.

Ike Nuss, December 7, 1902 discharged to mother."

So it took her three years and she got one a year.

Gates: That's right.

Sandberg: Wow.

Gates: She got all four of her children back one by one.

I mean just imagine the strength of this woman.

Sandberg: Yeah and what she must have gone through.

Gates: Sadly, Frieda wasn't able to enjoy her family for long.

She died of a heart condition in 1904, a year after she'd brought the last of her children home.

She was just 43.

Sheryl wondered if her children were sent back to the orphanage after her death.

The answer lay in a census for Manhattan, taken the following year... Sandberg: "Israel A. Nuss, head of household, 22, clerk.

Sarah is his sister, 20, she does housework.

Leopold, son, 18, clerk.

Isaac, son, 16, clerk.

Abraham, son, 11, at school."

Gates: This census says that your great-grandfather, Israel, as the head of household of three sons, but we know that's wrong.

These are his sibs... Sandberg: These are his siblings.

He took care of his siblings.

Gates: And 22-year-old Israel is the head of household.

Sandberg: Wow, with taking care of an 11-year-old.

Gates: Because both of his parents are dead.

Sandberg: Unbelievable.

Gates: And that's why they didn't go back to the orphanage.

Sandberg: Wow.

That's amazing.

Gates: Yeah.

Sandberg: And I don't I don't know if my family knew this because I don't think there was a very good relationship with Israel.

My mother was super close with her grandmother but not with him.

Gates: Not with him.

What do you think she'll make of this story?

Sandberg: I think, I think it'll give her greater understanding.

Gates: Yeah.

Sandberg: Yeah, it's nice.

But you know, the history of immigrants is this.

Think about what people go through today to immigrate.

They risk their lives, they're doing that for a better life for themselves and their family.

Sometimes that better life doesn't pay off for generations.

Gates: Yeah, that's right.

The paper trail had now run out for all three of my guests.

These are all the ancestors that we found.

Tomei: Oh, my God, skip, oh, my God.

Penn: Wow.

Sandberg: This is unbelievable... Gates: It was time to see what we could learn from their DNA.

We started with an admixture test, which reveals a person's ancestral heritage over roughly the last 500 years.

All right.

Please turn the page.

Can you read those percentages?

Tomei: Yes, 69.5% Italian.

Gates: What a shock.

All right, well let's see.

how Indian is Kal Penn?

Would you please turn the page?

That's the percentage right there.

Penn: Wow.

Gates: You're the most Indian Indian we have ever tested.

Penn: All right.

So, there's no British great-great-somebody?

Gates: In the woodpile, as it were, no.

Penn: All right.

Gates: How Jewish do you think you are?

We had actually... Sandberg: I think given this family tree I think Jewish.

I mean I don't know if anyone is 100% anything but it looks 100% but is anyone 100% anything.

Gates: Please turn the page.

Sandberg: Yeah.

I am 99.8% Ashkenazi Jew.

.1%, which I don't even know what that means, Southern European.

Gates: That's like noise.

Sandberg: I'm 100%.

Gates: The admixture results, for each guest, confirmed what we'd seen in their paper trail.

There was, however, one surprise still to come.

When we compared our guests' DNA to that of other people who have been in the series, we found a significant match for Marisa, evidence within her own chromosomes of a relative she didn't know she had.

Gates: You do match with someone who's been in the series before.

Tomei: Really?

Gates: Uh-huh.

Tomei: Oh, my God.

Gates: That means you're cousins.

You have long identical segments of DNA.

Isn't that cool?

Tomei: Yes.

Gates: Please turn the page and meet your genetic cousin.

Tomei: Julianne?

Gates: Yeah.

Tomei: Julianne?

Julie?

You know we went to school together?

Gates: Really?

I didn't know that.

Tomei: Yes, Jules.

Oh, I can't wait to tell her.

Gates: Marisa shares an identical stretch of DNA along her X-chromosome with her longtime friend, Julianne Moore.

Ironically, Julianne has no Italian ancestors that we know of, and every ancestor we could name on Marisa's tree has roots in Italy.

A powerful demonstration of how DNA can bridge the divide that appears to exist between people of diverse origins, providing a metaphor, of sorts, for our entire nation... and underscoring how most of us descend from ancestors who weren't born here, but who became a part of something that no one individual could ever have imagined.

The United States of America.

That's the end of our journey with Marisa, Sheryl and Kal.

Join me next time as we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests on another episode of "Finding Your Roots."

Merkerson: I've always wanted to know where we came from.

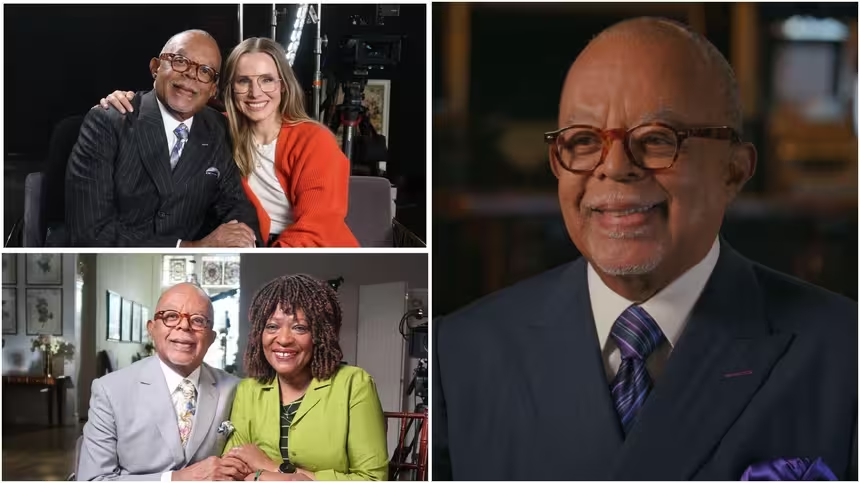

Narrator: Next time on "Finding Your Roots," talk show host Michael Strahan.

Strahan: Unreal.

Narrator: Actor S. Epatha Merkerson.

Merkerson: I'm blown away.

Narrator: History.

Gates: You're looking at the names of your family.

Narrator: Severed by slavery.

Strahan: It's unfathomable.

Merkerson: They have names.

Narrator: Ancestry restored.

Strahan: Holy... Gates: Isn't that amazing?

Narrator: On the next "Finding Your Roots."

Dreaming of a New Land Preview

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S5 Ep4 | 30s | Dr. Gates reveals the family history of Kal Penn, Sheryl Sandberg and Marisa Tomei. (30s)

Kal Penn | Where Are You From?

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S5 Ep4 | 1m 18s | Henry Louis Gates, Jr. reveals the family history of Kal Penn. (1m 18s)

Marisa Tomei | Surprise Celebrity Cousin

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S5 Ep4 | 1m 36s | Henry Louis Gates, Jr. traces the family history of Marisa Tomei. (1m 36s)

Sheryl Sandberg | Studying Resilience

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S5 Ep4 | 1m 11s | Henry Louis Gates, Jr. traces the family history of Sheryl Sandberg. (1m 11s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: